How Pneumonia Can Kill You & How to Prevent It

Pneumonia is an acute inflammatory process of infectious origin that affects the lung tissue. The microorganisms involved can reach the lung through different routes: micro aspirations of oropharyngeal secretions (the most frequent), inhalation of contaminated aerosols, by blood or by contiguity; and it coincides with an alteration of the defense mechanisms of the organism (mechanical, humoral or cellular) or with the excessive arrival of germs that overcome the defense mechanisms.

This disease can affect immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients and can occur outside or within the hospital (nosocomial), which greatly conditions therapeutic management.

Pneumonia represents an important health problem, which has motivated the main world health societies to periodically publish recommendations or clinical guidelines to facilitate its management and treatment.

Epidemiology of Pneumonia

Pneumonia is a common cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The annual incidence of it in adults in prospective studies is 5 to 1 case per 1000 people. It is more frequent during winter and in men older than 65 years. Outpatient mortality is less than 5%, if they are admitted to the hospital it is around 12% and can reach almost 40% in patients hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

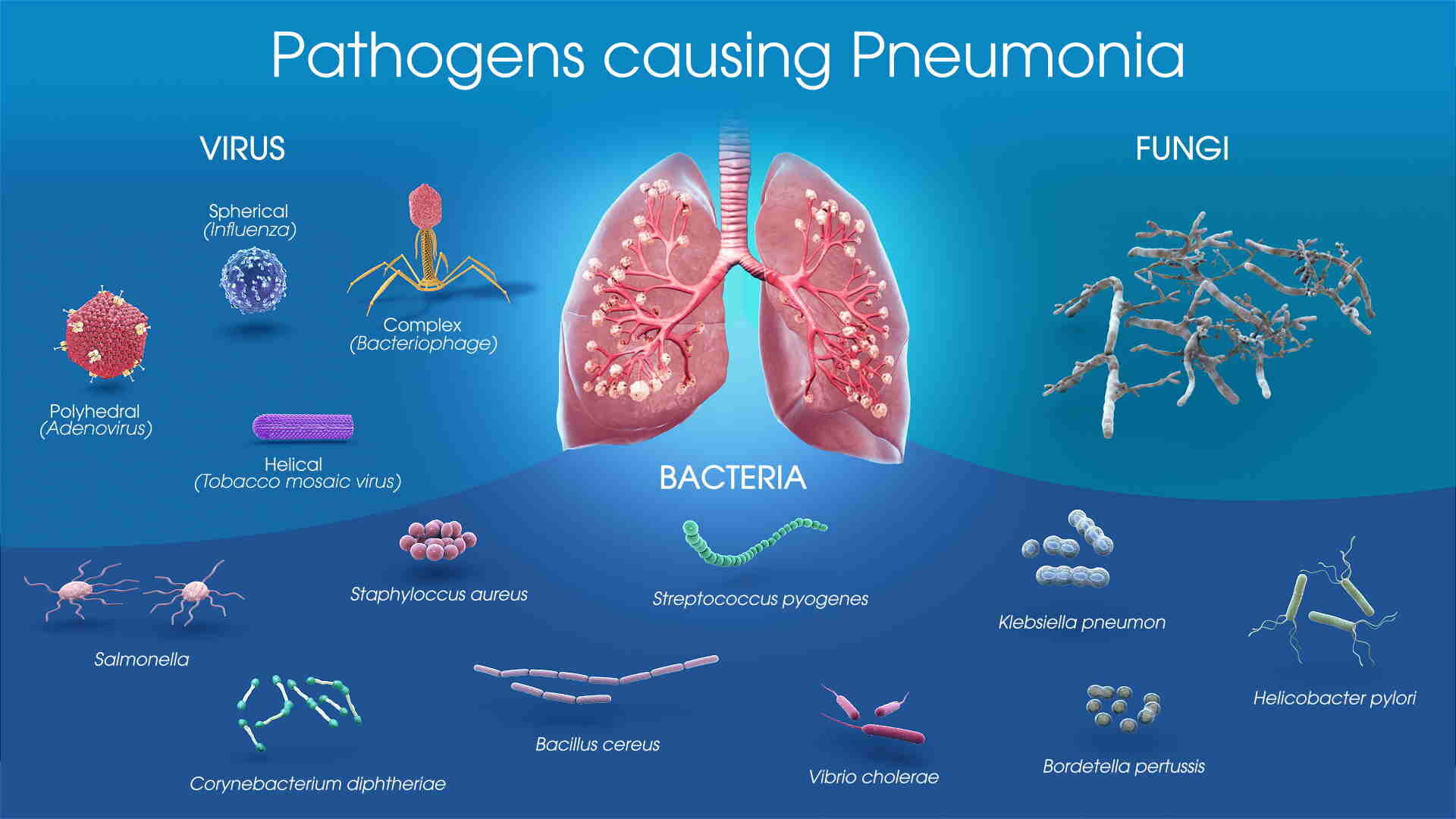

The etiological agents vary based on whether they are outpatients, hospitalized or admitted to the ICU, but Streptococcus pneumoniae remains by far the most frequent germ in all series and the one with the highest mortality. In outpatients, mycoplasma pneumoniae, viruses (influenza A-B, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus) and Chlamydia pneumoniae follow; in hospitalized patients, enterobacteriaceae, Legionella, and Haemophilus influenzae are added; and in those admitted to the ICU, Legionella, enterobacteriaceae and Stafilococcus aureus acquire greater importance. Germs are not identified in 40-60% of cases.

Know Your Risk

Pneumonia Pathophysiology

The airways are normally sterile from the subglottic area to the lung parenchyma. The lungs are protected from infection by a series of defense mechanisms, including anatomical and mechanical barriers (the filtration of air through the nostrils, the cough reflex, the sneeze, and the muco-ciliary apparatus), local factors and immunity (local secretion of secretory immunoglobulin A, complement, antiproteases, opsonins, lactoferrin, alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, and natural killer cells, in addition to the immune response mediated by the production of antibodies and specific cellular response, which neutralize and destroy microorganisms).

Infection of the lung parenchyma can occur when any of the defense mechanisms are altered or when the individual is invaded by a virulent germ. Bacteria reach the lower airways through inhalation of aerosols or aspiration of commensal flora from the upper airways. On some occasions, pneumonia is caused by microorganisms that reach the lung by hematogenous route, from another distant infectious focus or by contiguity in the case of liver abscesses, or by penetration in case of trauma.

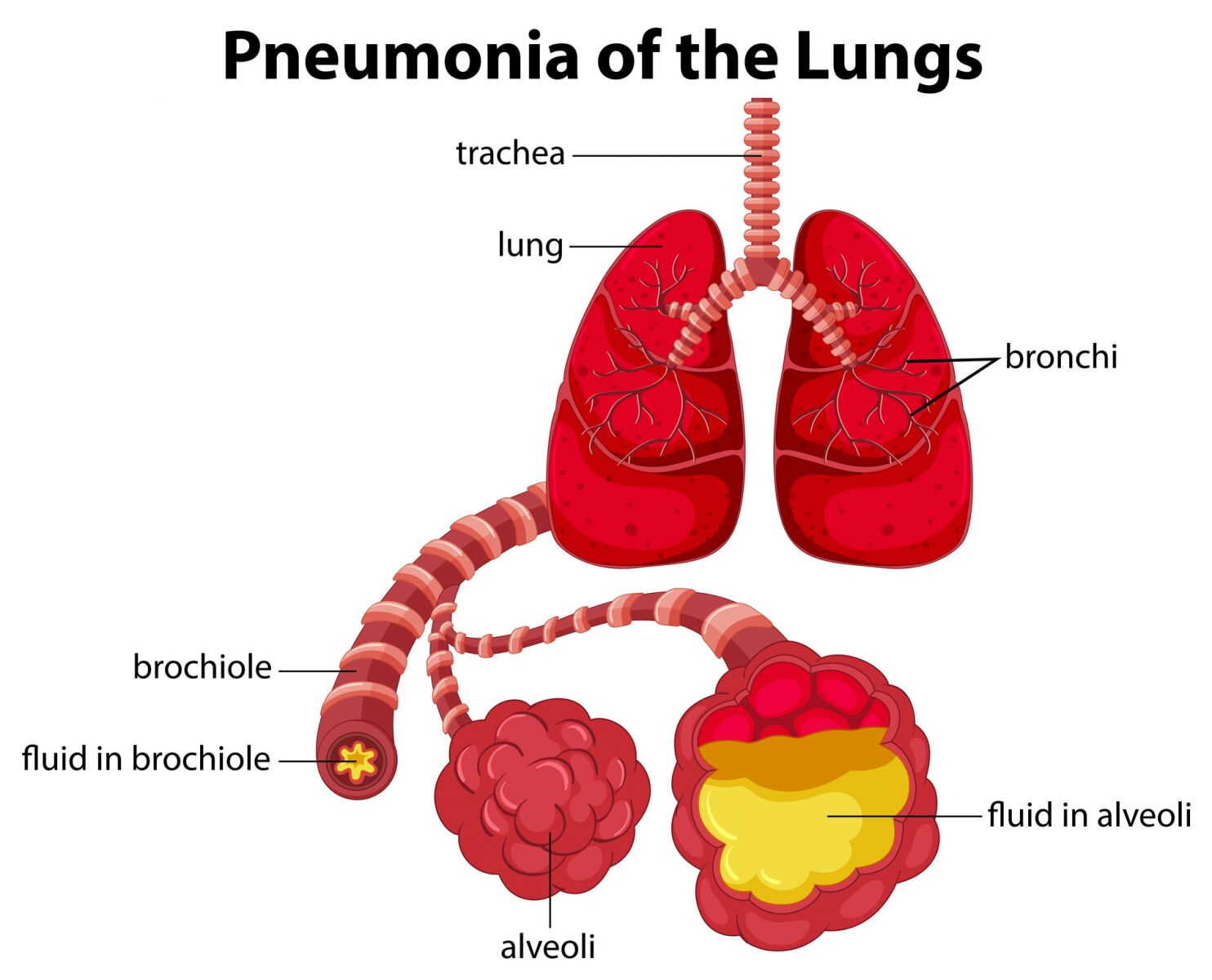

Bacterial invasion of the lung parenchyma initially leads to vasodilation, with increased cellular recruitment, this phase is called inflammation; Subsequently, congestion, and increased vascular permeability persist with the passage of intraalveolar exudate, fibrin deposition, and neutrophil infiltrate. This stage is known as "red hepatization." This phenomenon leads to increased shunt and perfusion ventilation disorders, which results in hypoxemia, and alteration in cardiac output. Then there is a predominance of fibrin deposits with progressive disintegration of inflammatory cells, this stage being called "gray hepatization". In most cases, consolidation resolves within 8 to 10 days by enzymatic digestion with reabsorption or elimination by cough at this stage is called "resolution". If the bacterial infection does not resolve quickly, the oxygenation of the blood is compromised and can lead to respiratory failure resulting in the death of the patient.

Source: Scientific Animations

Clinical Manifestations of Pneumonia

The main clinical manifestations of pneumonia are the presence of fever and variable respiratory symptoms.

Fever appears in most patients, most of whom have tachypnea and crackles on auscultation, and only a third show signs of consolidation.

Respiratory symptoms are nonspecific: cough, expectoration, dyspnea, and chest pain are the most frequent. The elderly may have fewer symptoms or be less severe than the young, and an acute confusion picture is common in them.

In young people without comorbidities, it has been pointed out that the distinction between “typical” and “atypical” pneumonia may be useful, suggesting as data of “typical” (pneumococcal) pneumonia: an acute fever with chills, rusty expectoration or mucopurulent, Pleuritic pain, cold sores, condensation semiology (tubal murmur), leukocytes> 10,000 or <4,000, and lobar condensation on chest radiograph with air bronchogram.

A more overlapping presentation, without chills, with dry or poorly productive cough and a predominance of extrapulmonary symptoms (atromyalgia, headache, vomiting, diarrhea) with variable auscultation can be associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia, Coxiella, and virus; and a mixed clinical picture, maybe due to Legionella infection, where the presence of hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia and hematuria is frequent.

Source: Harvard Health

Pneumonia Diagnosis

Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiography are essential to establish the diagnosis because similar symptoms can be seen in acute bronchitis and other non-infectious diseases. The radiological changes must be new and we can observe a single, patchy alveolar condensation (bronchopneumonia) or interstitial infiltrates.

X-ray is not useful to differentiate bacterial pneumonia from non-bacterial pneumonia, but it may suggest a specific etiology (tuberculosis, abscess), detect associated processes (endobronchial obstruction) or assess severity (multilobar involvement, pleural effusion).

Laboratory tests allow assessing the severity of the infection and deciding whether the patient will be managed on an outpatient or inpatient basis. The examinations carried out in the first instance are hemogram, general biochemistry, and pulse oximetry.

Microbiological diagnosis can be performed using invasive and non-invasive procedures. Microbiological identification is not usually necessary in outpatients, but an attempt should be made to obtain a microbiological diagnosis in all hospitalized patients.

Non-Invasive Procedures to Treat Pneumonia

Gram staining and sputum culture can be very useful for initiating empirical antibiotic therapy, especially if a rare or resistant pathogen is suspected.

Sputum culture is diagnostic if Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Legionella pneumóphila is isolated, although they require special media and are slow-growing. The cutoff point to distinguish infection from colonization in the expectorated samples or after tracheal aspiration in quantitative cultures is 106 CFU / ml.

Blood cultures are not very sensitive (4-18%) but specific, and their cost-effectiveness is currently being discussed. Its profitability is influenced by the previous taking of antibiotics in which case the positivity is less than 5%.

Know Your Risk

Invasive Procedures for Treatment of Pneumonia

Transthoracic fine-needle puncture is a simple, cheap, fast, and well-tolerated technique that does not require specialized means or personnel, has few complications: pneumothorax (<10%) and hemoptysis (1-5%) and can be performed at the head of the bed. It is not done in patients with mechanical ventilation. It is the most specific technique of all (100%). Its sensitivity varies between 33 and 80% depending on the type of patients.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is the most widely used technique in intubated patients, it has fewer risks than a transthoracic puncture, being more sensitive and less specific. This procedure requires specialized means and personnel.

In this procedure, the protected brush and bronchoalveolar lavage are available to perform quantitative cultures. Bronchial brushing has a sensitivity between 54 and 85% with a fairly high specificity ≥ 85%.

Bronchoalveolar lavage is less sensitive than brushing, but allows identifying intracellular microorganisms; It is the preferred technique in torpid pneumonia because it provides more unsuspected pathogens and alternative diagnoses, being particularly useful for the detection of P. carinii, mycobacteria, cytomegalovirus, nocardia and fungi.

Pneumonia Treatment

The initial treatment of pneumonia is empirical and will depend on the severity of the condition and the most probable etiology, establishing three well-defined groups: group 1 (home treatment), group 2 (hospitalized), and group 3 (ICU).

Pneumonia Outpatient Treatment

Previously healthy patients: Moxifloxacin or Levofloxacin orally for 7-10 days; o Amoxicillin + Macrolides for 10 days.

Patients with comorbidities: Levofloxacin or Moxifloxacin, or Amoxicillin / Ac. Clavulanic acid + Macrolides orally for 7-10 days.

Hospitalized Patients for Pneumonia

Cefotaxime or Ceftriaxone or Amoxicillin / Ac. Clavulanate + Macrolide, or Levofloxacin intravenously for 10-14 days.

ICU

Cefotaxime or Ceftriaxone at high doses + Macrolide or Levofloxacin intravenously for 10-14 days.

Prevent Pneumonia

Advances in the treatment of pneumonia are highly relevant; however, prevention has a primary place in this pathology. For this, the vaccine against S. pneumoniae (the main causative agent) and the influenza virus are currently available. The vaccine against influenza infection is included as a preventive measure because it has a significant impact on the incidence and mortality from pneumonia.

Influenza and pneumonia vaccines prevent serious infections mainly in older patients and other patients at risk, for this reason, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organization, consider vaccination in the patient hospitalized as an important measure for the prevention of morbidity and mortality.

There are three types of influenza virus: A, B, and C. Type A is more frequent and the one that causes epidemic outbreaks, presents a great antigenic variation of surface proteins, so each year, the World Health Organization indicates which strain will be used to prepare the vaccine, according to the one that has the highest probability of affecting the corresponding winter period.

The current pneumococcal vaccine is versatile, it is prepared from the capsular polysaccharides of the 23 serotypes that cause 80-90% of pneumonia with bacteremia. The efficacy of the vaccine is 75% to prevent bacteremia and pneumococcal meningitis.

Another important preventive measure is the modification of the risk factors that facilitate pneumonia, as well as the cessation of tobacco, which reduces the risk of suffering pneumonia in the 5 years after quitting by 50%.

Be protected from pneumonia with ongoing care, contact our office for more information.

Sources

1. Niederman MS, Mandell LA, Anzueto A, Bass JB, Broughton WA, Campbell GD, et al. Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163:1730-1754.

2. Barlett JG, Dowell SF, Mandel LA, File TM, Musher DM and Fine MJ. Guidelines from de Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:347-382.

3. Guidelines of the British Thoracic Society: Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. Thorax 2001;56 Suppl 4: 1-64.

4. Almirall J, Bolibar I, Vidal J, Sauca G, Coll P, Niklasson B, et al. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based study. Eur Respir J 2000; 15: 757-763.